Mapping the St. Lawrence

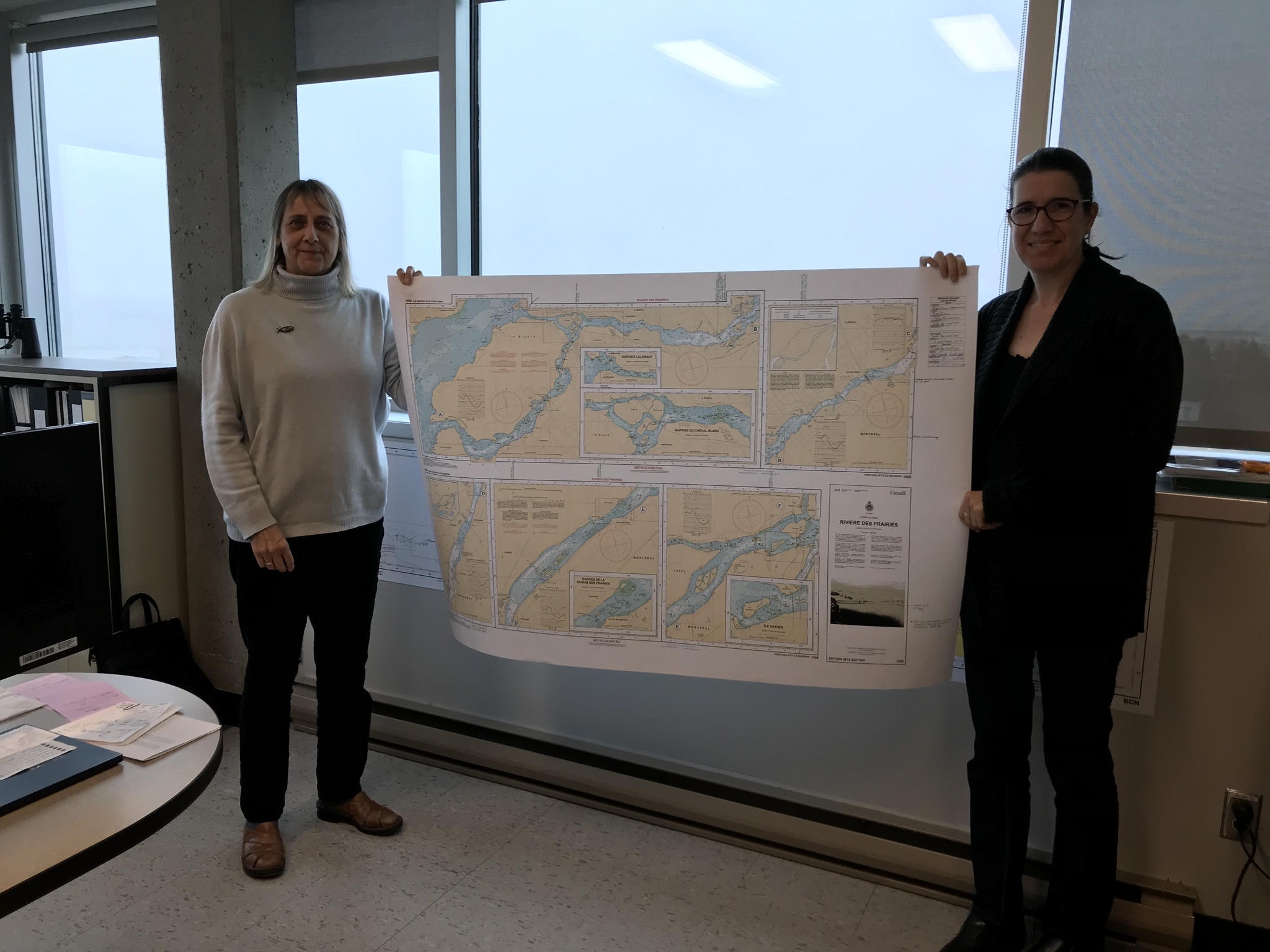

Cartography of the St. Lawrence had to be one of the first missions assigned to the Europeans who discovered the New World centuries ago, and it’s still actively practised today all along the St. Lawrence and its Gulf. Little known to the general public, the hydrographer’s vocation—now being revolutionized by technology—is to follow the constant changing underwater geography through currents, tides and storms.

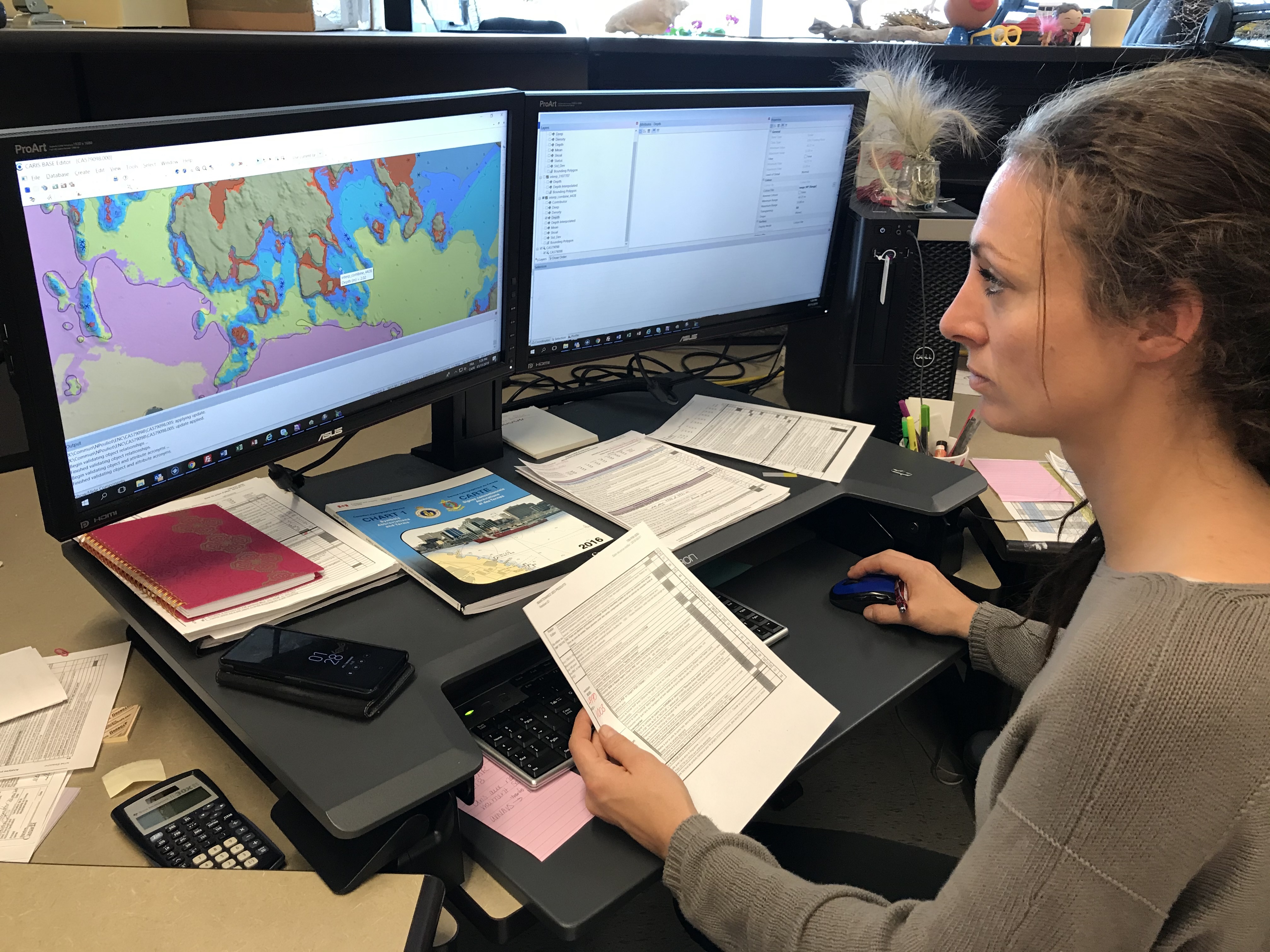

Versatile work

For Stéphane Paquet, a hydrographer with Fisheries and Oceans Canada for 32 years, it really is a job that takes you places. His time is divided between work in the office, on map production, and time spent on the river, documenting currents and tides and doing bathymetric surveys. To him, the choice is clear: “I’m a hands-on guy,” and over the course of his career, he has seen “lots of territory, been to the Arctic, Labrador, James Bay, Anticosti Island.” He calls conducting bathymetric studies “playing outside.”

For her part, Julie Larrivée is now a supervisor after many years of working in the field. “We train people to be able to work in every unit. All hydrographers are versatile. Depending on organizational needs, depending on what they want to do, they can be sent into the field or to the office. We maintain a high degree of flexibility.”

What does it take to get into this profession? “There’s no right or wrong training. What’s important is a basic education with some geography.” Candidates can come from a geomatics background to fields ranging from geography to civil engineering to forestry. Once accepted, the rest of the training is done in-house.

Endless exploration

Are there any grey areas left in the St. Lawrence? Surprising as it may seem, cartographers still don’t know much about certain areas. “Around Anticosti Island, in some parts of the North Shore and in the depths of the Gulf, we’re still using some data from as far back as 1930,” said Stéphane.

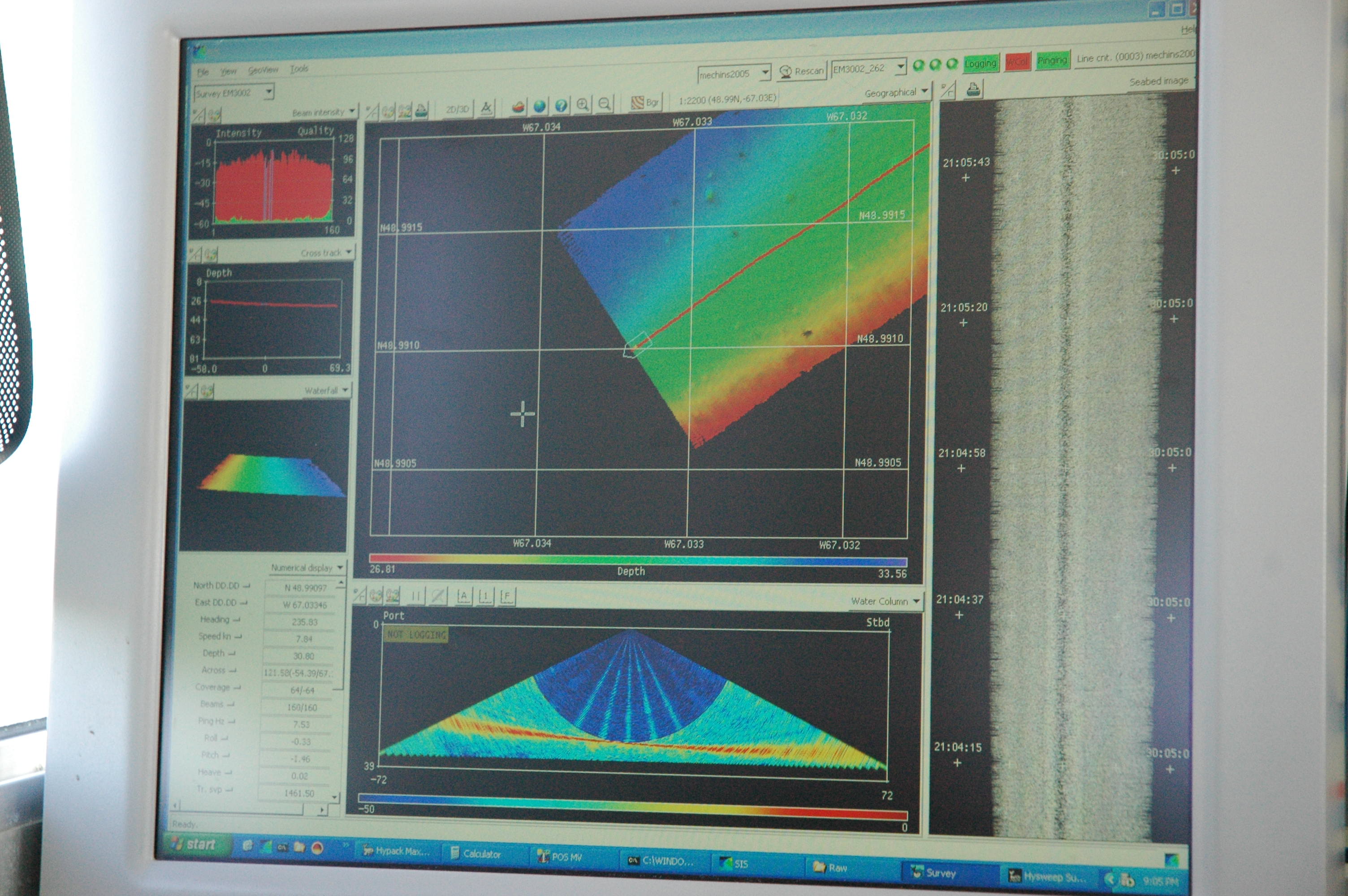

On a day-to-day basis, the most documented areas are the small ports located all along the coast, as well as the Quebec City-Montreal channel, which is mapped eight months a year. Is that repetitive? “Not at all,” he said. “It’s impressive to see how fast sand dunes can move under water. The river floor is always changing.” These surveys aim to identify danger zones, elevations, depths, wrecks and port infrastructure at all times, “anything that can be useful to mariners to locate and navigate safely.” In high traffic areas, every piece of information is crucial. “In some places, we can do six or seven soundings in the same year,” said Julie. This information is then circulated in the form of “Notices to Mariners” and is useful to everybody working on the river.

A constantly changing profession

What’s a necessary quality to do this job? “To be ready to learn,” said Julie. The rapid evolution of technology calls for staying on the lookout for changes and being proactive in learning. “It’s a daily challenge to stay up to date,” said Stéphane. “Software and techniques can change in as little as six months.”

Furthermore, since he started in the vocation, Stéphane has witnessed its incredible evolution. In the early days, survey results were recorded on a roll of paper, and mapping work was done by hand. “We would write names on the map with little self-stick notes, taking care not to end the day with those notes stuck on our elbows.”

Now it’s another world where everything is computerized. Aboard ship, sonars measure depth with sound waves. Aircraft use lidars—lasers—to accurately delineate coastlines and shallow areas that a traditional boat would not be able to explore. The data is available in real time and the charts appear in an electronic chart viewer. “All Notices to Mariners happen in real time.” The development of new standards will provide the ability to view and link new environmental information and obtain real-time under-keel clearance of vessels in electronic chart viewer and information systems.

There’s no end in sight to this occupational modernization. “Lots of innovation is going on in hydrographic acquisition right now,” Julie said. “Canada stands out in this field. We’ re at the forefront of technological advancement in marine cartography.”